Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

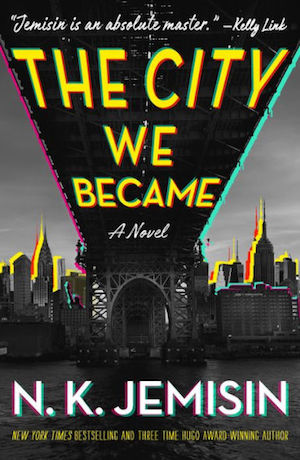

This week, we continue N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became with Chapter 5. The novel was first published in March 2020. Spoilers ahead!

“The click of a woman’s heels on the sidewalk. An old car’s bad timing belt, schoolgirls playing slaphands with a rhythm chant… all of it sets off something in my head.”

Chapter 5: The Quest for Queens

Manny and Brooklyn head for Queens, seeking its just-born avatar. The crosstown bus is taking forever to arrive, which gives them time to breathe and strategize. Brooklyn makes a phone call, then tells Manny that if her “hunch” is right, they’ll soon know what’s up with the Bronx.

More than hunches are involved in the boroughs’ awareness of each other, Manny realizes, no, feels. He’s hyperaware of Brooklyn’s presence. When she moves near him, space shifts, “its center of gravity adjusting in some way he cannot see or feel,” though he can taste the shift as a “bitter, metallic weight that makes his eyes sting and his nose burn and his ears itch a little.” In Weird NYC, Brooklyn’s “firmament of cityscape” changes to fit its new orientation to his “skyscraperness.” In normal NYC, she remains human, enviably unfazed by the heat and mosquitoes that plague Manny.

She identified Manny as Manhattan when passing a shop with display TVs that showed him cab-surfing on the FDR; they may need some image or name to focus in on their borough siblings. In the FDR news-clip, she could also see the invisible-to-nonavatars monster. Yet Manny’s roommate Bel could see the white tendrils in Inwood Hill Park. Cabbie Madison could see the FDR monster, and some motorists seemed dimly aware of it. He that they needed to see the extradimensional intrusions for their own survival. But there’s a more cynical explanation: Bel and Madison saw the intrusions because Manny needed them to. He wonders whether the city’s a true ally, whether he can assume he’s one of the “good guys.”

To Brooklyn’s renewed offer of lessons in “New-Yorkerness,” he bitterly asks if he has a choice. He does, she replies. To cut off his connection to NYC, he has only to leave it. Somehow Manny knows that if he does decamp, someone else will become Manhattan. “The city will go to war with the army it has, when that time comes.” Manny can’t decide whether he wants to be part of that army

The bus arrives. They board. Manny confesses his amnesia to Brooklyn. She confides that she now hears constant music, a symphony of the city, awakening the MC Free identity she deliberately abandoned. The city is remaking them. Being its subavatars means they can’t be ordinary people anymore.

Or as the Woman-in-White told Manny: You definitely aren’t human.

Using the MTA subway map, Brooklyn gives Manny his first New-Yorkerness lesson. The map’s how newcomers envision the city, some longtime residents too, but it doesn’t show NYC as it really is. For example, Staten Island is much larger than it’s shown. Staten Island didn’t want to be part of the city: it’s more like a small town, and its avatar’s likely to be “an asshole with a chip on their shoulder…and probably a Republican.” From her further descriptions, Manny intuits that in Queens they’ll be looking for a “hardworking non-techie,” in the Bronx a “creative with an attitude.”

They leave the bus for a rush-hour-packed subway train. Manny and Brooklyn feel a new “tickle of unbalanced gravity.” Looks like their Queens avatar is in Jackson Heights. Manny does a search for “weird Queens.” Several tweets mention “this old lady’s pool tryna eat her kids.” The associated photos show a pool with a strangely dark bottom, two flailing children, and a black-haired adult at pool’s edge. The black-haired woman “pulls” at them—they’ve spotted Queens!

Buy the Book

A Half-Built Garden

Brooklyn takes a phone call and announces that they’ve found the Bronx, too. She asked one of her councilperson’s aides to research a painting she remembered from a Bronx gallery. The mural is abstract, paint splashes and tangled lines crossing them in “dizzying profusion.” Manny realizes that “New York, the Really Real” portrays the “whole and distinct self” of NYC, the alternate reality he saw as empty. Now he understands that it’s actually crowded with people, “in spirit.” Understanding the image makes him feel another gravitic pull, to the north.

The mural artist is Bronca Siwanoy, director of the Bronx Art Center. Brooklyn and Manny debate whether to split up, one to find Queens, the other Bronca. Manny figures that going it alone might make them too vulnerable. They’d better look for Queens, since it looks like she’s in trouble.

Brooklyn reluctantly agrees. Manny studies a map on his phone and picks a spot that feels close to their sense of Queens. Then they’re off, “better late than never.”

This Week’s Metrics

Mind the Gap: Brooklyn catches on to the idea that public transit is a big part of city magic. The perfect balance of choice and chance, it has a rhythm all its own. Try saying it aloud, listening to the poetic trimeter: “Swap the N for the 7 at Queensboro Plaza.” Practically a spell.

What’s Cyclopean: My favorite adjective of the chapter is the “garblemouthed” street preacher.

The Degenerate Dutch: A search for “weird” plus “Queens,” trying to track down the borough avatar, first turns up complaints about drag queens in “poorly chosen ensembles.”

Anne’s Commentary

After the frenetic action in Inwood Hill Park and the tense restroom encounter at the Bronx Art Center, Chapter Five eases into a quieter exposition mode. The rush-hour pace of public transit lets Manny and Brooklyn recuperate from on-the-fly heroics and start figuring out how their sudden superhumanity works and how it will reforge their identities—how it’s already reforging them. Bronca evidently been given the Avatar Handbook; the other baby-boroughs have been relying on instinct and intuition. Even as he and Brooklyn begin the quest for Queens, Manny has no idea, beyond going to the borough in question, how to find a fellow avatar.

Manny knows avatars are hyperaware of each other in close proximity. He conceptualizes the way he senses Brooklyn’s presence and as shifts in adjacent space, adjustments to its center of gravity. You’d expect to feel this shift as you’d feel your chair lurch should the floor give way under one of its legs. Instead he experiences it synesthetically, tasting gravity along a scale from mild and sweet to bitter and metallic. When he’s in the alternate reality of “Weird New York,” he sees Brooklyn as her borough’s cityscape, himself as the “skyscraperness” of Manhattan; in this plane, their overlapping creates too much “mass and breadth” in one place, hence the “gravitic shifts.” But again, how to sense an avatar far from oneself?

Brooklyn starts off talking about “hunches,” then adds that you also need a “connection.” She shrugs as she uses the word; after all, she’s just an avatar-newbie like Manny. Manny wants to deny that finding each other could be coincidence, yet it’s exactly a coincidence Brooklyn describea. She took the train to Manhattan without knowing what she was looking for, then happened to see a TV news promo featuring some crazy dude riding the roof of a cab. Immediately, things snapped into focus, not only that the crazy dude was her goal, but that somehow he represented Manhattan as she represented Brooklyn. His video image was the connection. Which she coincidentally saw, right?

Oxford Languages defines coincidence is “a remarkable concurrence of events or circumstances without apparent causal connection.” The critical word is “apparent.” The person experiencing a coincidence doesn’t know what the causal connection may be, but probably senses that more than random chance is operating. Manny comes up with the idea that nonavatars like Bel and Madison can sometimes see Enemy manifestations when they need to for their own safety. But then why them and not the many more people oblivious to the Enemy? With the “calculating, brutally rational part of himself” that’s a remnant of his forgotten persona, Manny realizes it’s his need, not Bel’s or Madison’s, that gifts them with Enemy-awareness. He needs these people to survive so they can serve as his allies, or to put it with brutal self-honesty, his tools.

Manny takes self-honesty a step further. He gets “tools” because he himself is a tool of—the city. Brooklyn’s also a tool of the city, so when she needs a connection to find Manhattan, she gets one. And she gets a sense of his location as another “gift” of the city, of what the city’s remaking her into.

Manny further speculates that the city has “coldly stripped [his] identity from him”—except for those aspects it considers useful for this particular subavatar: a “pleasant exterior and the ability to ruthlessly terrorize strangers into doing his bidding.” He doesn’t like this idea. It could mean the city isn’t his ally. Worse, it could mean he isn’t “one of the good guys.” Unless these very doubts and worries indicate he’s a “good guy”?

If all this “weird-ass shit” is connected to the city, the way to escape it is to leave the city. Manny feels the truth of this assertion. Moreover, he somehow knows that if he runs anywhere else (perhaps recovering his memory on the way), the city will create another Manhattan avatar to march to war against the Enemy.

Is this somehow-knowledge accurate or… wishful thinking? The notion that going AWOL won’t weaken the city’s “army” gives Manny a moral get-out-of-NYC-free card. He can dodge that whole “with great power comes great responsibility” setback to superhero status. But does he want to dodge and run? He’s not sure.

In response to Manny admitting his memory loss, Brooklyn confides that she’s ambivalent about how becoming avatar-Brooklyn has plunged her back to hearing music all the time. She’s convinced she’s not MC Free anymore. That Manny initially hears this as she’s not free anymore has obvious significance. Brooklyn thinks they’ve both paid a price for avatardom: Manny his memory, she the “peace of mind” she associates with her “responsible” adult career.

Maybe these things aren’t a price exacted, though. Maybe they’re a bonus granted. Maybe Brooklyn hasn’t been free not being Free. Maybe Manny doesn’t want to risk remembering—becoming—who he was.

Brooklyn puts an abrupt end to their musings. They have to focus on Manny’s education and the search at hand. Manny’s learned enough to search local social media for anything “weird” happening in Queens, and bulls-eye: He’s rewarded with a connection to a kid-eating pool in Jackson Heights and the black-haired woman becoming Queens. Never rains but it pours – Brooklyn’s hunch about the Bronx avatar pans out, and they have a second target.

Kid-eating pools trump an artist not in immediate peril, they hope. Looks like the next chapter, featuring Bronca, will let us know if that hope was in vain.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

While I was writing Deep Roots, I got my father to tell me stories about 40s New York City under the guise of research. His Bronx was one of ball games in the streets, neighborhoods full of Yiddish radicals, and boarding houses. When I visited my Granny in Queens 40 years later, the city had changed—new waves of immigration, crime and grit (or perception of same), and white flight to the suburbs had all affected the demographics and personality of each borough. Twenty-first Century New York is something else again.

So what stays constant? My father isn’t “hard people” and my Granny never wanted a house with a back yard. At the same time, I’ve never had trouble imagining New York’s personality, or recognizing a New York attitude when I meet one. Jemisin’s got a hold of it—and yet the city still has too many aspects to capture in a cast of five. Does it matter that it’s the city of 2021 that awakens, and not the city of 1949 or 1985? How will it affect the avatars as the city keeps changing over the coming centuries?

Brooklyn and Manny ask themselves variants on those questions. The newborn entity is shaping them for its own purposes, and there are costs. That’s most obvious for Manny, who’s lost his memory and identity, but it’s not easy for those who haven’t been so reduced either. Brooklyn is being pulled back to an earlier form of herself, one she gave up deliberately. She has priorities that aren’t the city’s, and that she doesn’t want to sacrifice. We’ve heard the same from Bronca. Aislyn is likely to lose her family, if the Woman in White doesn’t steal her soul first.

Beyond that, the boroughs are an uneasy team—forced to work together to survive, yet often resentful and uncomfortable in each others’ presence. For Manny, Brooklyn’s gravity is “like sudden salt moving across the tongue.” It’s intriguing but bitter, stinging and burning and itching from “too much mass and breadth in one place at the same time.” We’ve heard the same from Paolo: cities are solitary creatures by preference, social by necessity. It’s not the most comfortable way to live in a hostile universe.

I appreciate that these “chosen ones” are thinking seriously about their choices. Is it worth the cost, to be part of something bigger? That’s pretty abstract—how about “is it worth the cost to keep eldritch entities from wiping out life on Earth?” It’s a hard thing to turn your back on. But then again, as Manny suggests, if you do the city will (probably) fill the gap you leave. New York has never depended on the presence of any one person. That anonymity is both blessing and challenge to the people who move through it, whether they enjoy getting lost in the crowd or seeking that crowd’s adoration.

So the chosen could choose otherwise. And what cost then? Maybe you’d remember that you decided not to help, or maybe you’d feel guilty about whoever took your place. Or maybe you’d forget the whole thing, just another suburban expat who didn’t appreciate life in the big city.

I’ve never wanted to live in the city myself. But I don’t know if I’d be able to resist Brooklyn’s symphony, “like tinnitus but beautiful.” I remember lying awake at night, hearing that rhythm coming through the walls of Granny’s little coop apartment. Turn it up to 11, and it would be hard to walk away.

Next week, Charlotte Perkins Gilman explains why the Time of Witching didn’t last longer, and how it happened at all, in “When I was a Witch.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden is now out! She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

When my monthly sf/f reading group discussed The City We Became, the most difficult point was trying to decide if the characters were avatars for the boroughs, or stereotypes thereof. I thought that the personas were still individual enough to be full personalities while exhibiting the “traits” of their associated sections of NYC. And yet, because an author can only do so much in one novel, there were dissents that the selected aspects for each borough made the characters into caricatures. Especially in the case of Aislyn/Staten Island. “Probably a Republican” did make me laugh, albeit ruefully.

I don’t know, I think some weird queens would be excellent allies in the battle to come.